Here’s why innovation can’t be managed using traditional methods.

We’re in an amazing time.

The rate of technological change and adoption gives consumers more choice and power than ever before.

For the consumer, this is awesome.

For big business, it’s a threat that must be navigated successfully.

Doing so means a new kind innovation management because the management most of us learned in school won’t quite do the trick.

During the industrial revolution, the question was — how can we produce what we know customers need as efficiently and cheaply as possible? Henry Ford’s great insight was that if he could reduce the cost of cars such that his decently-paid employees could afford to buy the automobile they made, he’d have a massive market. His very lean progressive assembly process was the result.

Today, the cost and time it takes to build, launch, and deliver new products at scale is lower than ever. The result is choice.

The number of competitors in most open markets is incredible and increasing rapidly. This means that consumers have more power than ever before. They have more companies to choose from, more models for each product, as well as vast quantities of information on quality, functionality, value, and so on.

The question is no longer how can we produce more, but how can we discover and create new value before someone else does?

The former isn’t obsolete – there is a proven demand that needs to be met. But, when you try to innovate and create new demand using “modern management” for optimizing supply, don’t expect to be around forever.

Efficiency In Supply: Relics of the Industrial Revolution

How can companies produce more, faster and more cheaply?

In the past, the answer was to treat people like cogs, like a component of the progressive assembly line. We could then analyze, dissect, and re-organize the moving parts to optimize a manufacturing process’ efficiency.

This process worked best with relatively simple products with few differentiating factors between models and well-understood market demand.

Cascading management hierarchies told workers what to do, and they did it.

The proper amount of coal on your shovel, the amount of coal you had to shovel in a minute, and the tool you used to shovel the most coal into the furnace. All were studied and adjusted to “perfection.”

Businesses grew by creating and optimizing known processes in a known market. This wasn’t just for the product, but for the entire company.

The structure mirrored that of the assembly line with each department representing a cell: manufacturing, marketing, sales, support, and back-office functions.

At a time when the question was how can we produce what we know customers need as efficiently and cheaply as possible, this worked extremely well.

But, when companies need to adapt and innovate to keep demand high, a narrow focus on optimizing existing operations doesn’t help much.

The fact is, there might be room for a bigger win when you reinvent instead of merely continuously improving – you can attempt to continuously improve, but you will be optimizing in a local maximum.

Efficiency suffers when customers require increased customization and differentiation.

In other words, a wide variety of models to fit a range of needs.

The Toyota Production System largely grew out of this dilemma, attempting to leverage the “leanness” of Ford’s production system is a world of increasing complexity and market differentiation.

Waterfall

Have you ever heard this response to a new idea?

“Let’s do it! Go scope it out.”

Next thing you know, there’s a “fool-proof” plan of who’s doing what, when they’re doing it, how long it will take, and then how much it will cost.

Once the plan is approved and budgeted — execute.

Projections are based on past experience. “Finished” is arbitrary and determined by internal negotiation on features.

Employees once again act merely as cogs in carrying out the plan, and their performance is measured based on adherence to the projections. This makes sense for some products where the market is well-understood, and the solution is well-known and fixed.

Unfortunately, this approach stacks the odds against you when facing any uncertainty. It fails because it precludes adaptation based on new information. Adherence to the plan becomes more important than success.

The result is millions of dollars and thousands of man-hours spent building a product someone senior thought was a great idea, but not the market.

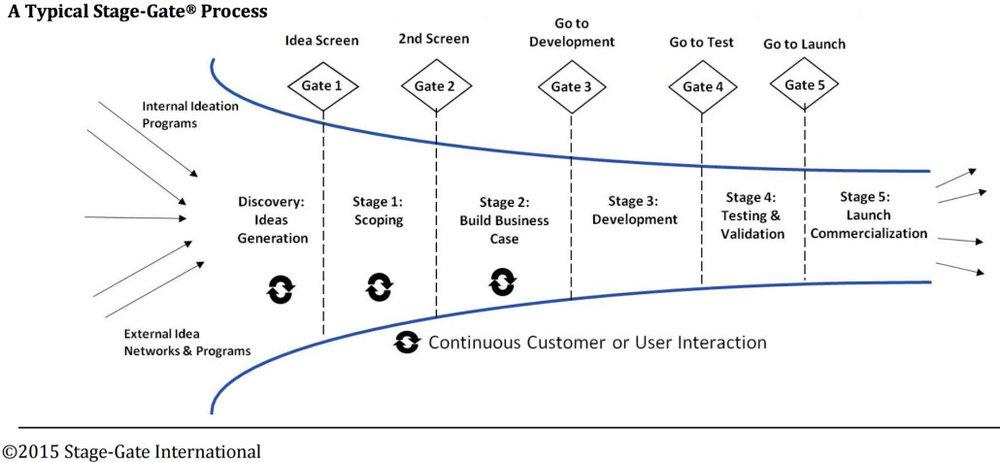

Unfortunately, waterfall is characteristic of Stage-Gate Innovation, too.

Idea, then scoping, then evaluating and justifying based on historical “evidence,” then developing.

Stage 4 brings testing and validation, though this is typically testing for technical risk (does it work?), not market risk (will it succeed in the market?).

Furthermore, even if an organization tests in the market at this point, the development costs have already been spent!

The relics of the industrial age– good business execution practices — are being used in product development, commercialization, and innovation, despite the fact that we know full well that innovation is fraught with uncertainty.

The New Wave of Innovation Management Paradigms – Efficiency in Discovery

When facing uncertainty, we need processes that allow us to optimize learning, not just execution.

Methods are needed that focus on the customer experience, allow us to adapt to new information, and help us make decisions based on market-based evidence.

Agile

The agile manifesto, which was introduced in 2001, prioritizes short product development “sprints” in order to incorporate new information which might come from a variety of places such as new technology, customer input, insights, or development issues.

Instead of assuming that businesses know exactly what the customers need and then build the product heads-down over the course of months or years, they can release versions quickly and incorporate customer response.

Design Thinking

Centered around customer empathy and prototyping, design thinking is a compelling framework for ideation and the discovery of new value.

Instead of believing that we know what our customers need, as we attempt to serve them — why not seek to learn what they need through a variety of techniques that build customer empathy?

When it comes to harnessing creativity, design thinking does wonders by providing a source of inspiration based on a deep customer understanding.

Lean Startup

The key insight of Steve Blank, “the founder of Customer Development”, is that we can “develop” customers in the same way we develop products: through an iterative, learning approach.

Rather than assuming we know how to market and sell new products to new customers, we should learn first.

Eric Ries combined Customer Development with Agile, creating an elegant loop that connects customer learning with sprint-based product development: Build, Measure, Learn.

This is Lean Startup.

Lean Startup applies the idea of “eliminating waste” from lean manufacturing with the fact that in innovation, we don’t know what will succeed. Since building something that people don’t use is wasteful, why don’t we figure out what people need before and while we build it?

Lean Innovation

Lean Innovation is built upon the foundations of design thinking and Lean Startup tailored for the enterprise.

The three core principles of Lean Innovation are what we like to call the 3 E’s: Empathy, Experiments, and Evidence. (We dive deeper into the 3 E’s in our 5 Ways to Spark Innovation at Your Organization – download available below.)

The beauty of Lean Innovation is that we don’t need to have ideas in order to begin discovering and evaluating opportunities because we can begin with interviewing customers to build empathy.

As insights are gained and consistencies emerge, teams can begin experimenting with different solution ideas to iterate toward a product with proven market viability. At every step of the process, teams experiment to gain a deeper understanding of the market, validate their path, and justify future investment based on evidence rather than gut feeling or traditional market research that is not optimized for innovation.

Leading companies like GE and Intuit are reporting great success, and we are seeing the same with both our enterprise and social impact clients.

Conclusion

Society evolves.

We’re witnessing global technological and economic transformation.

Our organizations have gone digital, but our corporate structure and processes are still analog. They were born in the Industrial Age, but we are no longer there. Our management techniques and our “people and processes” must also evolve.

In uncertain, volatile, and customer-dominant markets, we must transform our cultures to be responsive to their needs.

We must utilize innovation management combined with a lean business model, instead of trying to manage innovation using traditional means. We must optimize discovery and learning while maintaining our ability to execute.

Awareness of how our current operating procedures grew out of the Industrial Age can set us free to innovate.

Gone are the days of innovation by internal planning and product scopes. The day of the customer is here.

Both the enterprise and social impact organization should exist to discover, create, and deliver new value.

An organization’s ability to learn and translate insight into action rapidly is the ultimate competitive advantage.