The first time I was advocating the idea of a dual innovation approach, here also referred to as organizational ambidexterity, is now more than 5 years ago. At this time it became pretty obvious to me that this concept – academically worn-out but deficiently or not at all put into practice in most organizations – would be of increasing importance in the time to come. It turned out compelling to me, given the inherent conditions a large company operates in, that decoupling explorative innovation (such as the development of new-to-the-company technologies and/or business models) from innovating the existing core business is mandatory for an organization in order to establish a balanced and sustainable innovation capability. As recently outlined, I consider organizational ambidexterity to be a key innovation issue for organizations in 2016 and beyond. And it looks like I have a point here…

After being discounted by many innovation practitioners in my sphere for some time, the concept of organizational ambidexterity is now finally gaining traction with rising speed. It’s encouraging to see a couple of research studies, recently conducted by different well-known consulting firms, backing the ideas I’ve been passionately supporting for many years. Let’s sum up some relevant findings of these studies, making the case for dual innovation management:

BCG: Most Innovative Companies 2014

Evaluating breakthrough innovation cultures and organizations, BCG concludes in their annual 2014 study:

By definition, breakthrough innovation is the introduction of new ideas that drive a different way of doing things. This requires risk taking, of course, since no one can foresee the outcome or results of such initiatives. Breakthrough innovators are willing to make decisions and choices as much on the basis of intuition and insight as on data and forecasts – they bet on people rather than manage a process.

In our experience, a dedicated environment is required to promote this kind of approach. And indeed, across all companies and industries, there is a growing trend toward a centralized approach to innovation and product development – meaning that these functions and processes are either controlled and driven by a centralized organization, or a centralized organization conducts R&D and passes the framework for new products and services to business units or regional units for development and launch. This trend is even more pronounced among strong innovators, with those pursuing a centralized approach rising from 68 percent in 2013 to 71 percent in 2014. Similarly, about 70 percent of disruptive innovators also lean toward a more centralized approach. Two-thirds of all breakthrough innovators stated that all innovation and product development is controlled and driven by a centralized organization, at least in its initial stages. More than 70 percent have a different organizational entity for managing radical innovation. (…)

Another approach enjoying increasingly wide trial is the corporate incubator. Incubators more or less evaporated when the dot-com bubble burst, but BCG research indicates that they are making a comeback – with a twist. The new generation of incubators is focused on incubating ideas that can have a direct impact on the sponsoring company’s business, not just creating stand-alone companies. The start-ups selected for incubation have interactions with their corporate sponsor that go beyond simple cash support, including access to R&D, supply chains, and important customers at both the corporate and the business unit levels.

Accenture: 2015 US Innovation Survey

Accenture finds in their recent study that companies need to reassess their approach to innovation execution:

Companies need to develop agile innovation operating models that enable companies to not only test new ideas quickly, but also absorb new capabilities and talent from other industries. Flexibility is especially important, considering how many of today’s innovations have no organizational home. Companies that cling to rigid innovation approaches are more likely to fail at creating space for disruptive innovation or nurturing new ideas.

A two-engine operating model holds particular promise for companies looking to achieve flexibility, as well as higher returns from their innovation investments. With this dual model, innovation engine 1 is laser-focused on making existing products and capabilities continually better. Engine 1 supports a company’s steady pace of evolution, and is a critical enabler of the incremental changes that propel a business forward. Innovation engine 2, on the other hand, drives big-bet innovations such as the introduction of entirely new product or service categories, an expansion into new markets, or the development of a new business model. Engine 2 efforts are disruptive and potentially game changing. When executed correctly, these innovations deliver a step-change improvement in organizational performance and competitive advantage.

Deloitte: Radical Innovation and Growth – Global Board Survey 2016

The latest Global Board Survey from Deloitte, brought to my attention by Paul Hobcraft, also calls for a dual innovation approach by establishing a dedicated “Division-X”, separated from core business and reporting to the board:

Our experience tells us and substantial research sustains (eg. 2014, Salim Ismail, Exponential Organization) that making new business creation inside a corporation is hard and often doomed to fail. The “immune system” of the core operation is soon to take over any great idea that might cannibalize it and thus even if the right decision is to disrupt yourself from within, it is almost impossible in practice.

We therefore want to know how many companies actually own a so-called Division-X or the equivalent of one (a division with the goal of finding radically new products or services). If they own one, we want to know for how long they have been in operation. 22% of respondents say “yes”, leaving 78% to say “no”. 30% of those with a Division-X have had one only for a year, 27% for two years and 24% for 5 years. 17% have owned a Division-X for 10 or more years. A correlation between turn-over, size, operation and industry reveal that these are largely midsized to very large companies from 1) Consumer Products & Services, 2) Technology/Media/Telecom, and 3) Industrial. (…)

Whereas, it is too early for the relatively sparse sample of global boards having experimented with a Division-X to harvest their fruits we are truly delighted to find that 75% of the companies that report an above 10% growth expectation for the coming 24 months also own a Division-X (or the equivalent hereof).

Detecon: Die Innovationskultur von Konzernen (2016)

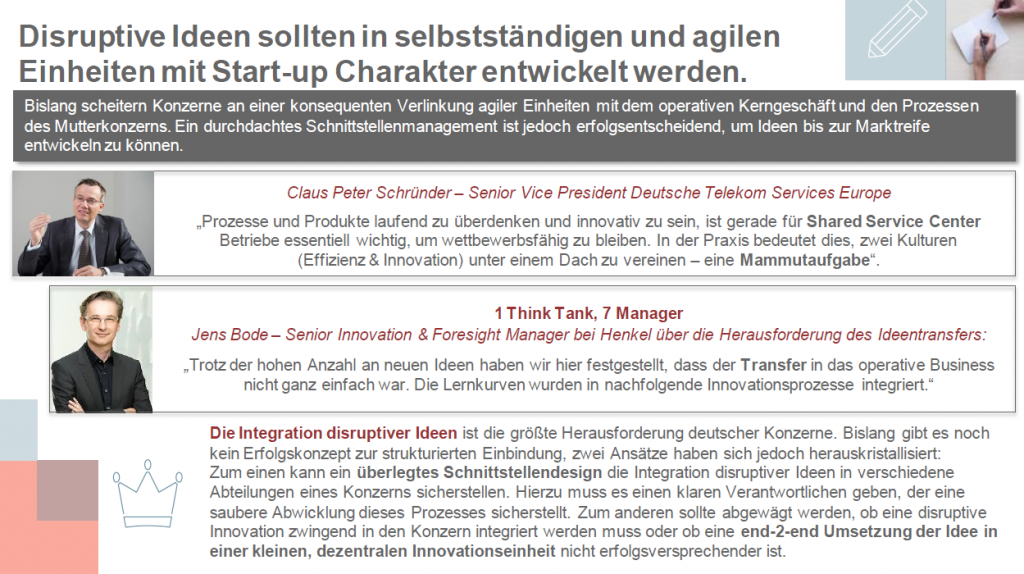

The german consulting firm Detecon just published a study (in german) based on interviewing and surveying more than 70 german corporate innovation experts. Some of the findings were:

- 100% of the surveyed experts agreed that defining an ambidextrous innovation strategy is an important management responsibility and critical to corporate innovation capability.

- Explorative initiatives and strategies should be pursued in dedicated units, decoupled from core business.

- The integration of disruptive ideas is the biggest challenge in german corporations. How can interfaces between dedicated units and core business be properly designed in order to develop disruptive ideas up to commercialization?

Conclusion

Taken together these outcomes, there hardly seems doubt anymore that appropriate ambidextrous approaches to innovation are required for most established organizations in order to stay competitive. In fact, it’s now a question of how they can be adequately organized, governed and operationally implemented. While the aforementioned studies clearly make the case, if not an imperative, for dual innovation management, they still lack a more detailed advice on the implementation issues. Jeffrey Phillips aptly comments on the recent Accenture study:

Accenture’s recommendation, the two engine solution, is appropriate but not new. Their suggestion is to define a path for incremental ideas, and a separate methodology and philosophy for radical or disruptive ideas. In this manner the ideas would be treated differently. What’s missing is a portfolio approach, which would indicate how many ideas of each type are valuable or necessary. (…) But until there’s clear sponsorship for disruptive ideas, funding and risk tolerance for those ideas and clear metrics and measurements, all ideas will eventually become incremental.

Another critical issue to be elaborated in each individual case is how to set up a dedicated unit for explorative innovation (vs. exploitative innovation in core business) in terms of its scope and openness. While the traditional notion of “ambidextrous organizations” assumes a strong “inhouse” focus, where exploration is mainly fed through internal strategic initiatives, ideas and intrapreneurship, a modern understanding of organizational ambidexterity also involves an appropriate degree of external engagement and co-creation, in particular by means of collaborating with startups. Michael Docherty also gets this point straight in his recent call for a “hybrid innovation engine for growth“:

We need to move beyond the myth of the ‘ambidextrous’ organization – large companies need to work on transformative innovation both internally and through engagement with the startup ecosystem. Learn to embrace disruption through collaboration.

In the past, systematic dual innovation management approaches have often been discounted due to falling short of expectations or lacking prevalence across the sum of companies. Both reasons, however, don’t necessarily imply the basic concept is inappropriate or even wrong. Adequate buy-in on part of executive/senior management and proper implementation of these approaches are mandatory prerequisites in order to make them live up to their potential and – as a consequence – increasingly trusted and applied. The above studies clearly reveal: Organizational ambidexterity proves to be a necessary condition for outstanding corporate innovation capability. Company boards may ignore it at their peril.

Takeaway

Let’s stop arguing whether dual innovation and organizational ambidexterity are required in today’s business world. Apart from a couple of exceptions, they seem mandatory for the majority of organizations, facing increasing pace for required reinvention and adaptation to changing environments. Instead, let’s shift our focus on how those approaches can get properly implemented in order to deliver much-needed impact. Going about this issue particularly entails

- accounting for dual innovation in strategy definition

- providing management sponsorship and well-suited organizational anchoring of dedicated exploration units

- decoupling of leadership, funding, staffing and metrics between exploration unit and core business

- balancing separation and integration between exploration unit and core business

- organizing operational interplay and designing proper interfaces between exploration unit and core business

- defining complementary innovation scopes for exploration unit and core business

- driving explorative innovation through a balanced portfolio of internal and external initiatives

- applying well-suited tools and processes for exploration initiatives

In my previous post, I have started attempting to sort out my view of a model for modern, dual innovation management. How can we get essential organizational ambidexterity from myth to going? I look forward to your ideas and thoughts!

2 Responses to The Case for Dual Innovation