The need for speed

Let’s face it, we live in a time where we expect everything done quickly. We praise the fastest sprinter, crave the fastest race cars, expect the fastest service, and demand the fastest Wi-Fi. But why are we so thrilled with speed? And does first or fastest always equate to the best?

Psychologists and philosophers believe that as humans we are addicted to the dopamine that is released from adrenaline spikes when we’re put into a fight or flight situation. And that the invention of the automobile has given us a taste of the speed we inherently crave.

And it’s no different in the business world. Speed and growth have become the gods of Silicon Valley, with ‘move fast and break things’ as their leading mantra. This concept of growth at all costs is less risky for disruptor brands than it is for large corporate giants. Nevertheless, it has infiltrated Fortune 500 conference rooms.

Most companies today have started to embrace this need for speed by jumping on new ways of working, inspired by startup culture, like Design Sprints, Accelerators, and Hackathons. The problem isn’t the speed of these techniques (which we actually love and practice ourselves), but rather as they become more popular and widely accessible, there is a greater chance of them being misled or misused. As the saying goes, there is no silver bullet for innovation. And a fast approach that is more ‘innovation theatre’ than impact won’t solve all your company concerns.

Innovation speed traps

In reality, going too fast has its downside. By innovating too fast, you may find yourself ahead of the times. Here are three common innovation speed traps:

Innovation before its time

Probably one of the most infamous ‘before its time’ launches was the EV-1 from General Motors. It was released in 1996 when electric vehicles felt like something straight out of the Jetsons. But the market (and the infrastructure) wasn’t in a place to embrace this new innovation. Ultimately, only 2,500 of the vehicles were made and the plus was pulled (literally) in 1999.

Speedy mistakes

By innovating too fast, you also open yourself up to making mistakes. Take for example WeWork, who sold a concept of a coworking space that would change the world, without ever stopping to measure whether the model was still optimally positioned to win.

Death by pivot

Everyone talks about companies that have failed because of stagnation and not innovating enough. But what about companies that changed too quickly due to being too reactive? I call this death by pivot.

Flowtab was a great idea in theory; it allowed bar patrons to order and pay for drinks quickly, using their smartphones, with a central tablet at the bar managing orders. Unfortunately, neither bars nor patrons wanted to pay extra for the service. So, Flowtab attempted to pivot to sell advertising to alcohol producers. After that failed, they tried yet another pivot, pitching to sports stadiums, but another competitor had already beaten it to the punch.

Slow innovation is having a moment

So why not embrace going slow?

In many cultures, ‘slow’ is seen as a dirty word, with connotations of being lazy, a slacker, or giving up. But slow doesn’t have to mean ineffective. We shouldn’t mistake activity for achievement.

In reality, some of the most successful companies of our time master this concept of ‘slow innovation.’ Apple is famous for not inventing new products, but perfecting them (e.g. the original MP3 player was actually created by Rio in 1998, with the Apple iPod hitting shelves in 2001). Apple also plays with speed by adding friction into the process of getting their products, with many consumers waiting overnight in line to get their hands on the latest release. Subsequently, consumers value that product even more since they had to put in more time and effort to obtain it.

And there are companies like Ball Corporation, who were strategic about their evolution from a wooden bucket company to a glass jar company, to a metal can company, to a plastic bottle company. What held the organization together for more than 100 years was its overarching identity as the world’s greatest container organization, without becoming too reactive to the latest threat or trend.

How to decelerate

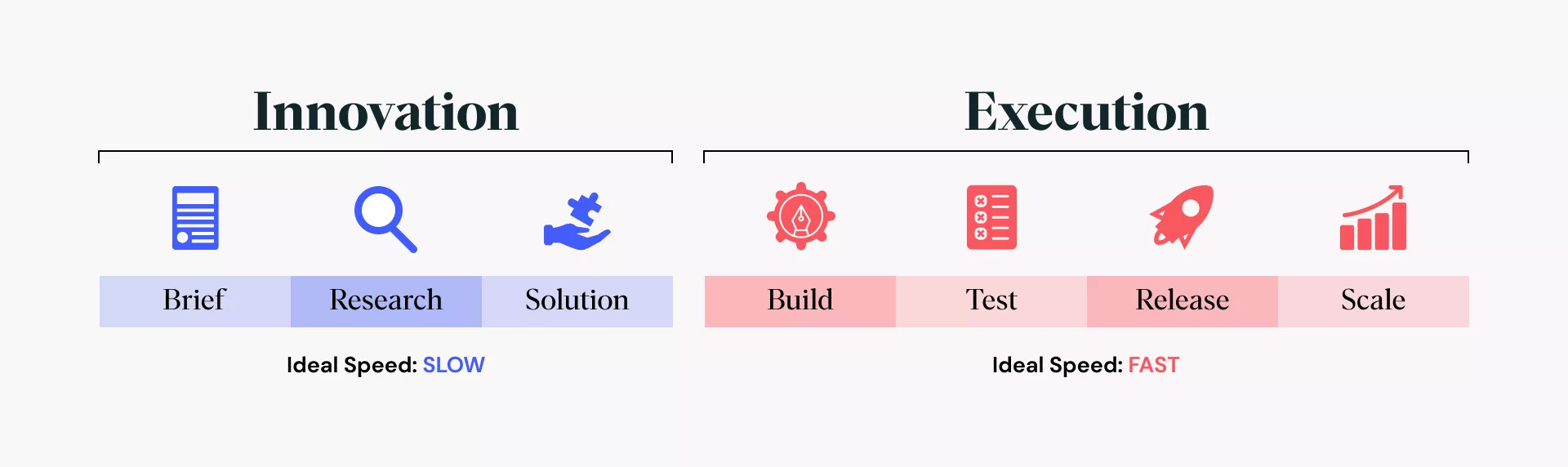

Sure, you may be thinking, well my company can’t go any slower when it comes to innovating. But in my experience, it’s the execution part of the journey where companies are usually going too slow. Rather than taking the time to do their due diligence in the upfront innovation process, they often jump straight into ‘solutioning’. This involves investing lots of money and resources into market research to reinforce business-first thinking.

Instead, I’d like to propose embracing an old Latin proverb, Festina Lente, which means let your body and movements be quick, but keep your mind at a graceful, reasonable pace. This takes the thoughtlessness and blind impulsiveness out of speed, and translates it into something healthier: skillful quickness. Or in other words, to “hurry slowly”.

And here are three ways in which you can do just that:

Far too often we force solutions to market, without stopping to consider if we’re still headed down the right path or if the world in which we operate has changed since the brief was made.

When it comes to slow innovation, the key is to create space in your process to pause and reflect on changing context. You can do this by restructuring governance as a time to challenge thinking, not to share updates on progress, or to “sell in” ideas. At Board of Innovation, we recommend facilitating a discussion at key points in the innovation funnel to debate whether a solution should “pause, pivot, kill, persevere” according to a series of guiding principles. Or experiment with creating an innovation culture comfortable with moving backward, not just forward.

Another opportunity to practice slow innovation is by embedding systems thinking into your process. Systems thinking is the ability to take into account all potential impacts and ripple effects that a solution may cause, by looking beyond the walls of the company and thinking a situation through the full ecosystem. Map all the players and stakeholders, internal and external, and develop contingency plans for both winners and losers in order to ensure the long-term sustainability of new innovation.

You can read more about how we approach systems thinking here.

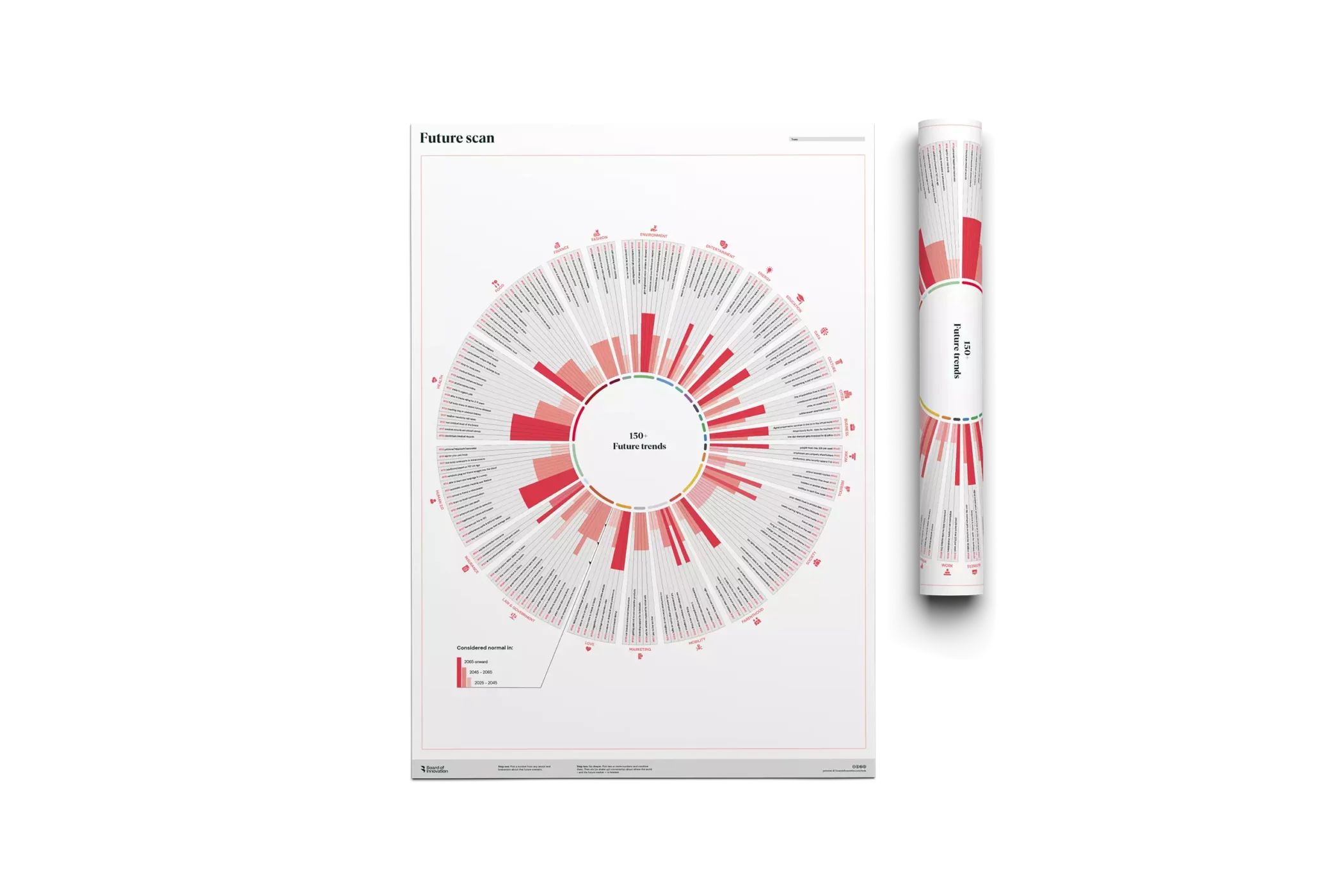

Finally, the biggest opportunity to embrace thinking slow within your company or team is also arguably the hardest. Take the time to regularly scan for signals of change in an effort to identify opportunities as they emerge, not just reacting to them when they’ve become too big to avoid. This requires a behavioral shift, starting by establishing rituals that monitor for shifts in the outside world; this will allow you to switch your strategy from defense to offense – but that’s a story for another blog post.

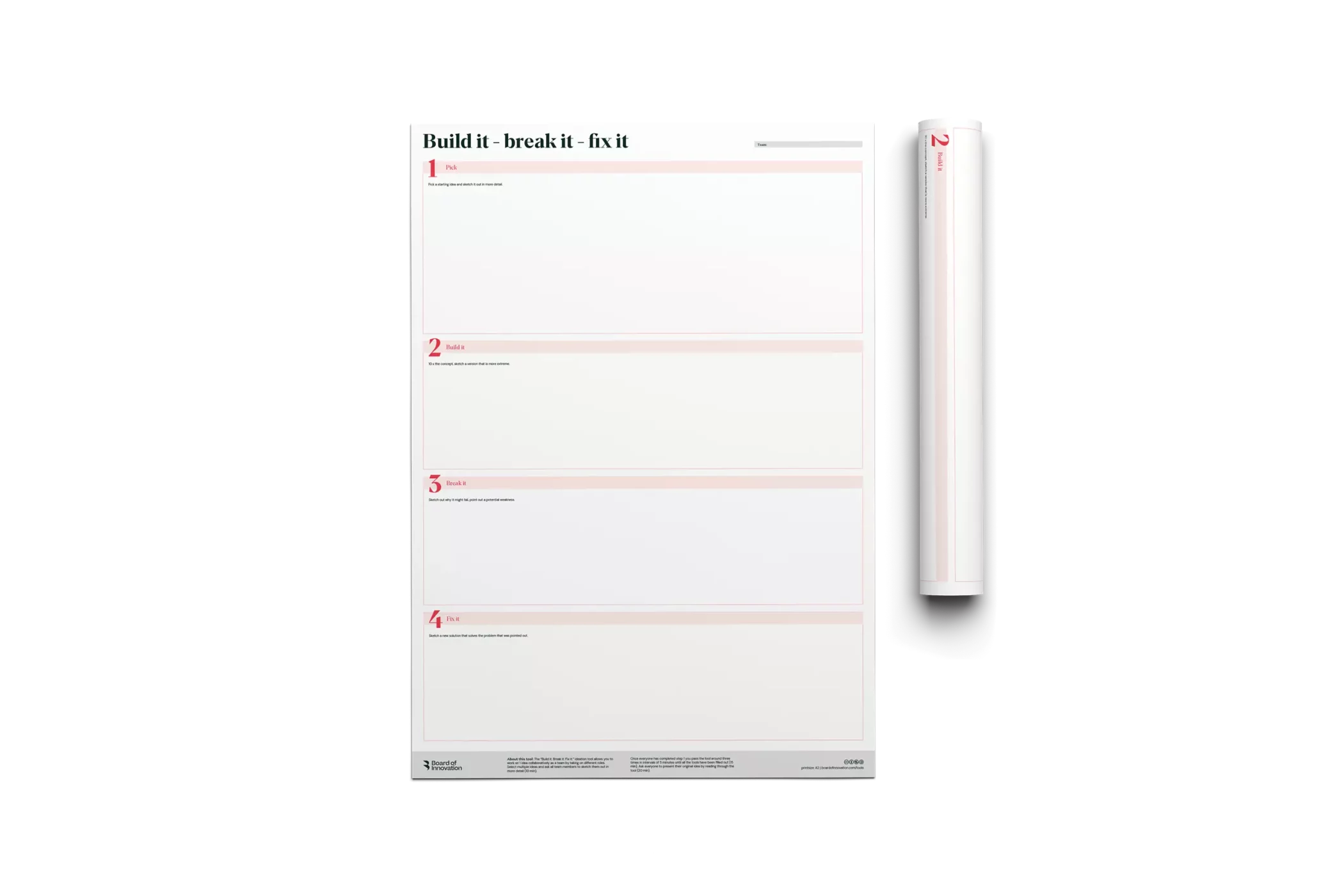

Build it, break it, fix it toolkit

Use this tool to debate your ideas and test their strengths

We offer practical innovation resources and tools to help you innovate

Now practice

Now that you’ve learned a little bit about the concept of deceleration, I encourage you to practice it for yourself as we can all use a bit of slowing down in this high–speed world. It’s about balancing your Type 1 Thinking (intuition) with Type 2 Thinking (logic, analytics, and rigor). This way, you will be less prone to error, less reactive, and less emotionally biased towards new innovation, and ultimately speed up your ability to execute more quickly in the end.

Want more?

Interested in learning more about how you may “slow down” your company’s approach to innovation? Reach out to us!