Avoiding innovation errors through jobs-to-be-done analysis

July 7, 2015 12 Comments

The lean startup movement was developed to address an issue that bedeviled many entrepreneurs: how to introduce something new without blowing all your capital and time on the wrong offering. The premise is that someone has a vision for a new thing, and needs to iteratively test that vision (“fail fast”) to find product-market fit. It’s been a success as an innovation theory, and has penetrated the corporate world as well.

In a recent post, Mike Boysen takes issue with the fail fast approach. He argues that better understanding of customers’ jobs-to-be-done (i.e. what someone is trying to get done, regardless of solutions are used) at the front-end is superior to guessing continuously about whether something will be adopted by the market. To quote:

How many hypotheses does it take until you get it right? Is there any guarantee that you started in the right Universe? Can you quantify the value of your idea?

How many times does it take to win the lottery?

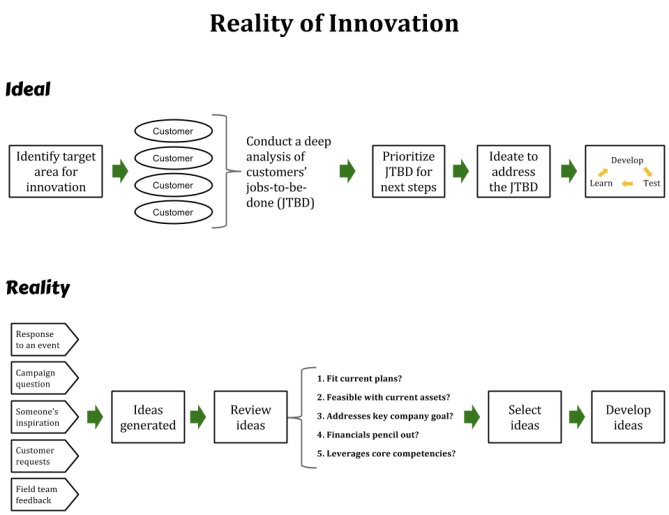

Mike advocates for organizations to invest more time at the front end understanding their customers’ jobs-to-be-done rather than iteratively guessing. I agree with him in principle. However, in my work with enterprises, I know that such an approach is a long way off as a standard course of action. There’s the Ideal vs. the Reality:

The top process – Ideal – shows the right point to understand your target market’s jobs-to-be-done. It’s similar to what Strategyn’s Tony Ulwick outlines for outcome-driven innovation. In the Ideal flow, proper analysis has uncovered opportunities for underserved jobs-to-be-done. You then ideate ways to address the underserved outcomes. Finally, a develop-test-learn approach is valuable for identifying an optimal way to deliver the product or service.

However, here’s the Reality: most companies aren’t doing that. They don’t invest time in ongoing research to understand the jobs-to-be-done. Instead, ideas are generated in multiple ways. The bottom flow marked Reality highlights a process with more structure than most organizations actually have. Whether an organization follows all processes or not, the key is this: ideas are being generated continuously from a number of courses divorced from deep knowledge of jobs-to-be-done.

Inside-out analysis

In my experience working with large organizations, I’ve noticed that ideas tend to go through what I call “inside-out” analysis. Ideas are evaluated first on criteria that reflect the company’s own internal concerns. What’s important to us inside these four walls? Examples of such criteria:

- Fits current plans?

- Feasible with current assets?

- Addresses key company goal?

- Financials pencil out?

- Leverages core competencies?

For operational, low level ideas inside-out analysis can work. Most of the decision parameters are knowable and the impact of a poor decision can be reversed. But as the scope of the idea increases, it’s insufficient to rely on inside-out analysis.

False positives, false negatives

Starting with the organization’s own needs first leads to two types of errors:

- False positive: the idea matches the internal needs of the organization, with flying colors. That creates a too-quick mindset of ‘yes’ without understanding the customer perspective. This opens the door for bad ideas to be greenlighted.

- False negative: the idea falls short on the internal criteria, or even more likely, on someone’s personal agenda. It never gets a fair hearing in terms of whether the market would value it. The idea is rejected prematurely.

In both cases, the lack of perspective about the idea’s intended beneficiaries leads to innovation errors. False positives are part of a generally rosy view about innovation. It’s good to try things out, it’s how we find our way forward. But it isn’t necessarily an objective of companies to spend money in such a pursuit. Mitigating the risk of investing limited resources in the wrong ideas is important.

In the realm of corporate innovation, false negatives are the bigger sin. They are the missed opportunities. The cases where someone actually had a bead on the future, but was snuffed out by entrenched executives, sclerotic processes or heavy-handed evaluations. Kodak, a legendary company sunk by the digital revolution, actually invented the digital camera in the 1970s. As the inventor, Steven Sasson, related to the New York Times:

“My prototype was big as a toaster, but the technical people loved it,” Mr. Sasson said. “But it was filmless photography, so management’s reaction was, ‘that’s cute — but don’t tell anyone about it.’ ”

It’s debatable whether the world was ready for digital photography at the time, as there was not yet much in the way of supporting infrastructure. But Kodak’s inside-out analysis focused on its effect on their core film business. And thus a promising idea was killed.

Start with outside-in analysis

Thus organizations find themselves with a gap in the innovation process. In the ideal world, rigor is brought to understanding the jobs-to-be-done opportunities at the front-end. In reality, much of innovation is generated without analysis of customers’ jobs beforehand. People will always continue to propose and to try out ideas on their own. Unfortunately, the easiest, most available basis of understanding the idea’s potential starts with an inside-out analysis. The gap falls between those few companies that invest in understanding customers’ jobs-to-be-done, and the majority who go right to inside-out analysis.

What’s needed is a way to bring the customers’ perspective into the process much earlier. Get that outside-in look quickly.

Three jobs-to-be-done tests

In my work with large organizations, I have been advising a switch in the process of evaluating ideas. The initial assessment of an idea should be outside-in focused. Specifically, there are three tests that any idea beyond the internal incremental level should pass:

Each of the tests examines a critical part of the decision chain for customers.

Targets real job of enough people

The first test is actually two tests:

- Do people actually have the job-to-be-done that the idea intends to address?

- Are there enough of these people?

This is the simplest, most basic test. Most ideas should pass this, but not all. As written here previously, the Color app was developed to allow anyone – strangers, friends – within a short range to share pictures taken at a location. While a novel application of the Social Local Mobile (SoLoMo) trends, Color actually didn’t address a job-to-be-done of enough people.

A lot better than current solution

Assuming a real job-to-be-done, consideration must next be given to the incumbent solution used by the target customers. On what points does the proposed idea better satisfy the job-to-be-done than what is being done today? This should be a clear analysis. The improvement doesn’t have to be purely functional. It may better satisfy emotional needs. The key is that there is a clear understanding of how the proposed idea is better.

And not just a little better. It needs to be materially better to overcome people’s natural conservatism. Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman discusses two factors that drive this conservatism in his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow:

- Endowment effect: We overvalue something we have currently over something we could get. Think of that old saying, “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”.

- Uncertainty effect: Our bias shifts toward loss aversion when we consider how certain the touted benefits of something new are. The chance that something doesn’t live up to its potential looms larger in our psyche, and our aversion to loss causes to overweight the probability that something won’t live up to its potential.

In innovation, the rule-of-thumb that something needs to be ten times better than what it would replace reflects our inherent conservatism. I’ve argued that the problem with bitcoin is that it fails to substantially improve our current solutions to payments: government-issued currency.

Value exceeds cost to beneficiary

The final test is the most challenging. It requires you to walk in the shoes of your intended beneficiaries (e.g. customers). It’s an analysis of marginal benefits and costs:

Value of improvement over current solution > Incremental costs of adopting your new idea

Not the costs of the company to provide the idea, but those that are borne by the customer. These costs include monetary, learning processes, connections to other solutions, loss of existing data, etc. It’s a holistic look at tangible and intangible costs. Which admittedly, is the hardest analysis to do.

An example where the incremental costs didn’t cover the improvements is of a tire that Michelin introduced in the 1990s. The tire had a sensor and could run for 125 miles after being punctured. A sensor in the car would let the driver know about the issue. But for drivers, a daunting issue emerged: how do you get those tires fixed/replaced? They required special equipment that garages didn’t have and weren’t going to purchase. The costs of these superior tires did not outweigh the costs of not being able to get them fixed/replaced.

Recognize your points of uncertainty

While I present the three jobs-to-be-done tests as a sequential flow of yes/no decisions, in reality they are better utilized as measures of uncertainty. Think of them as gauges:

Treat innovation as a learning activity. Develop an understanding for what’s needed to get to ‘yes’ for each of the tests. This approach is consistent with the lean startup philosophy. It provides guidance to the development of a promising idea.

Mike Boysen makes the fundamental point about understanding customers’ jobs-to-be-done to drive innovation. Use these three tests for those times when you cannot invest the time/resources at the front end to understand the opportunities.

I’m @bhc3 on Twitter.

Hutchmeister,

Reviving the old blog, are we? Getting bored, frustrated, (/whatever….)?

Good to see you active and engaged in the real world once again whatever the reason.

So let me try and take just a moment to critique (productively – is the intent).

You do remember Steve Jobs, as in “Think Different”, right?

Start by changing the center diamond to “Is it different?” rather than “Is it better?”. If it’s better, incumbents are going to come to hunt and kill you. OR you’ll succeed in making incremental changes to a given paradigm and get old while playing leapfrog with the stupids on the other side(s). And it will become even more challenging to get out then than now.

If it’s different, they may not even notice that you’re there. (Unless you’re looking for an exit, that’s a good thing.) AND it’s gets you a base to go back to in case you enter (or are dragged into) that fray prematurely.

There’s more we can fix, but I thought I’d hit the super-obvious (and intuitively appealing) one first.

Welcome back.

Rick

Thanks Rick – I love when you stop by here.

I’m in agreement re: different. But that’s got a couple issues as a primary basis of analysis:

1. Different is the realm of invention, it’s the creative muse. But it’s not really the first principle. Let’s take bitcoin as an example. It’s quite different. But is it better than the incumbent solution? I argue it’s not. The Segway was quite different, and received praise from Steve “Think Different” Jobs when he saw it; see #3 in this post:

Did it materially improve existing jobs-to-be-done? I think an argument could be made that it did, and that perhaps it really failed on JTBD test #3 (value > incremental costs).

My point is that ‘different’ is useful, but I wouldn’t replace ‘better’ as the primary metric.

2. ‘Different’ is a squishy standard. ‘Better’ can be determined with some rigor. ‘Different’? I guess you can estimate the quantity of ‘different’. Given your rationale for ‘different’ – that it flies under the radar of incumbents – it seems you’d have to understand human psychology to know when someone would ignore a nascent challenge to your business/products/services.

Hutch

Hi Hutch and thanks,

I didn’t mean to imply that different was a slam dunk. On the contrary I’d say that for ‘different’ the odds will not only still be against you, but probably even more so at the beginning. But if you get past that hurtle, the rest of the trip is far more certain than if you’re fighting for a position in line – and particularly so if you want/need to get to the top spot.

Segway isn’t as good of an example of different as BTC and actually BTC is just a front for blockchain – and as soon as it gets two more features (enforceability and reversibility), given what it is (an alternative means to robustly facilitate/present/record transactions of any kind, including kinds that don’t yet exist and/or aren’t yet prevalent) its going to blow the doors off of everything it touches.

So then to squishy – different product (cheaper, better looking, whatever) gets you points, different process (easier to use, faster diffusion to becoming ubiquitous) gets you more points, and different paradigm bestows home field advantage. The paradigm associated with Segway wasn’t even close to being different – we’ve seen lots of motorized personal transportation vehicles emerge and evolve over time.

The paradigm associated with reliance on an independent distributed system (blockchain) for validity and anonymity, however, is so far away from the way we do things today that the two can almost not see each other. Yet blockchain can and will provide for a superset of today’s needs and in so doing, will make the other obsolete before it has time to take a second breath.

Thoughts? & Take Care.

Love it Rick. And actually, I did do a JTBD takedown of bitcoin, but I also wrote that blockchain holds promise:

My preferred order of “hoops” if you will: (1) significantly better; (2) different. And I’m not overly concerned about different. Segway was radically different than other transportation systems. It just didn’t find a job-to-be-done where it could replace the incumbent solutions. The iPhone was different, although it certainly shared a lot of similar features. But it ended up killing competitors, until Android came along. Waze shared a number of features with other map apps, but it added the IoT aspect of tracking speeds and re-routing you.

‘Different’ is nice, but I’m not convinced it’s a primary criteria. But…I’m open to evidence to the contrary!

Hutch

Hutchmeister,

‘Better’ by definition constrains you to some slice of the existing market (market “share” as it were) because i’s not defined outside of the existing market.

Conversely “different” allows you to transcend the existing market (and all of its constraints). It’s a Blue Ocean vs Red Ocean decision.

In a Red Ocean you’re fighting harder and harder for a larger part of what will inescapably become a smaller and smaller pie, all the while becoming increasingly wed to the paradigm associated with that pie.

In the Blue you can be unopposed – the keys to success in the Blue Ocean are (1) the flexibility to pick up and move whenever necessary or beneficial (the opposite of becoming wed to a given paradigm) and (2) the wisdom to launch markets using technologies and business models that are either expandable and/or transferable to currently underserved markets.

The Segway was always going to be a Segway because the adjacent markets were already quite occupied and served. Blockchain has (and I’m quite sure will) expand the definition of transaction into areas that one wouldn’t even serious consider serviceable in those terms today.

The iPhone was about the worst telephone ever made for voice communication, but it was the only phone that allowed mobile interaction with network constructs which connected people outside of the constraints associated with the point-to-point paradigm associated with personal communication since the days of the telegraph.

I mean, it’s your choice – you can think you’re better than everyone else in a given game and hope to have enough luck on your side to become the best for long enough to save up a pension for the day when you’re not (or it’s not). Or you can elect to become good at finding and providing for needs which remain unfilled, in which case (given that there’s always more still to do than has already been done) you’ll be working (and likely increasingly profitable) until you decide to quit.

You’re not so old as to have already forgone that choice. At least I hope not.

Take Care my friend.

Thanks Rick. I’ll differ with your interpretation of “better” in this context. Jobs-to-be-done are fundamental. No matter what innovation you’re bringing to market, it needs to address someone’s JTBD.

Did the iPod provide better outcomes than the Sony Walkman? Yes, yes it did. The existing “market” is people who want to listen to music on the go. There exists a job-to-be-done for independent parties to verify transactions. That JTBD is the market. Blockchain can provide better outcomes, principally in cost, time and privacy. In this case, “better” means addressing the same market, but providing improved outcomes.

So I don’t see that focusing on “better” limits you to the current feature set that serves a market. No, not at all.

Make sense?

“Better”, Hutchmeister – is only one very limited (unidirectional) vector within the larger domain of “Different”. The key point of Christensen’s work was to prove that many times “worse” can make 2Bdone that are even more important than the jobs currently being served visible and even predominant, thus Disrupting the product, process, and paradigm previously thought of as most important.

Sony (and it’s customers) prided in the Walkman’s high fidelity given its portability. MP3 on the other hand was also portable, but was (and still is, although to some lesser extent) inordinately “lossy”, which is the diametric opposite to high fidelity. Per the standard used by incumbent producers and their customers, the iPod was grossly inadequate. But once discovered and served, the market for the ability to buy and play or repeat any single track from any musician in any order far outweighed the prior vaunted performance characteristics and Sony (and it’s entire supply chain, which included the record producers and distributors of that day) lost that war big time.

The same happened with cellular telephony. Although the phased “can you hear me now” has become cliché’, the prime characteristics by which Bell differentiated itself (and the standards imposed on equipment they once forced their customers to buy) was also fidelity – and to this day, the fidelity of cellular telephony falls far short of even the least demanding specification that was in place for land lines. And we all know how that went as well.

Attempting to surpass that which the incumbent and the current market consider important (the metric by which “better” is defined), will bring upon you, the entrant, nothing but than the ire, (and put you in the crosshairs) of a well-resourced incumbent community which you seek to displace from it’s highest-margin customers. Moreover, unless the entrant has established a beachhead and can support themselves on the basis of a product or service outside of the traditional venue (in other words, something ‘different’), incumbent customers will continue to buy the name-brand (traditional) product for long after the time by which an entrant needs to establish themselves to remain even viable, much less be thought of as ‘better’.

I must say that your remaining so stalwart in conventional conviction – despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary – reminds me a lot of the ‘party line’ that those who are (/have become) highly dependent on incumbent interests have become obligated to support. Hutchmeister, tell me it isn’t so.

w/ Regards and Respect, as always.

I do believe we’re interpreting “better” quite differently. For instance, your point regarding the Walkman and its high fidelity. You make the point that MP3 was lower quality, that it was not “better”.

When I say “better”, I’m talking about fulfilling the outcomes of getting a job done. Sure, many times that can be even better features. But that’s just one aspect of “better”. Better serving the outcomes that matter is what I’m talking about. Not better performance on features.

I have an analogous post on my blog here. It’s about how the poor quality of phone cameras was just fine. Why? Because they were much better positioned to capture moments. People carry their phone with them everywhere. They don’t lug cameras around. The basis of “better” in this case wasn’t megapixels. It was being able to capture moments at any time. The post:

That’s what I mean by “better”. Not simply improvements on feature performance.

Hutch

Hutchmeister, I’m good with that.

The problem is that the measurement (and conventional definition) of ‘better’ invariability revolves around metrics known (or accepted) to be “better” on the basis of polls of (and/or sales to) existing customers, which invariably evaluate along the lines of conventional performance measures and shun even entertaining much less accepting the idea that “different” might be in some way beneficial. Without discovering and developing the appropriate type of “different” (an iterative process at best), one can never get to that which is truly best.

(Sorry, neglected to add the following important info – denoted in CAPS – to the prior response.)

The problem is that the measurement (and conventional definition) of ‘better’ invariability revolves around metrics known (or accepted) to be “better” on the basis of polls of (and/or sales to) existing customers, which invariably evaluate along the lines of conventional performance measures and shun even entertaining much less accepting the idea that “different” might be in some way beneficial, PARTICULARLY WHEN THAT WHICH IS DIFFERENT REQUIRES SACRIFICE OF PREVIOUSLY PRIORITIZED PERFORMANCE MEASURES ALREADY ACHIEVED. Without discovering and developing the appropriate type of “different” (an iterative process at best), one can never get to that which is truly best.

Pingback: 16 metrics for tracking Collaborative Innovation performance | I'm Not Actually a Geek

Pingback: Why Amazon wins | Innovate the core, innovate to transform | I'm Not Actually a Geek